Could it be the Viking spirit that spurred on a small Swedish furniture and home-furnishing business to become a global giant by establishing 460 stores in 62 markets around the world? Just what is it that has enabled IKEA to become one of the most successful global companies from its humble beginnings in rural Sweden? Read on to learn how Nordic values and Scandinavian pragmatism have helped drive the successful global expansion of this flatpack phenomenon.┬Ā

Nordic values ŌĆō and value for money

IKEA, one of the greatest success stories to come out of Scandinavia in the past few decades, embodies some of the most important Nordic values: it is straightforwardly unshowy (if persistent), democratically inexpensive (comparatively) and pragmatically practical (unless, like me, you are exceedingly clumsy with self-assembly), yet has a good eye on quality and design elegance.┬Ā┬Ā

One company slogan from 1981 ran, ŌĆ£Like Sm├źlandŌĆÖs farmers, our values are down-to-earth.ŌĆØ It could be said that IKEAŌĆÖs cheapest furniture may not be of the finest quality, but when compared with what you might pay somewhere else, itŌĆÖs more than good enough for many people. Many of the storeŌĆÖs utensils and home accessories are exceptionally good value and quality. But only once you add the magic of Nordic designer chic do you get a winner like IKEA.┬Ā

Humble beginnings

By now itŌĆÖs well-known that IKEA is named after the initials of its founder, Ingvar Kamprad, and those of the farm he grew up on, Elmtaryd, and his hometown, Agunnaryd. WhatŌĆÖs less well known is that the initial investment came from KampradŌĆÖs father, who had promised to give the young Ingvar a monetary reward for passing his exams with decent results in 1943.┬Ā

After a decade of trading, two important things happened in 1953: the first showroom opened in ├älmhult, Southern Sweden, (apparently so that sceptical customers could come and see that the quality was good despite the low price) and the company adopted the concept of selling its furniture flat-packed for customers to assemble at home.┬Ā┬Ā

IKEA designer Gillis Lundgren, who designed the BILLY bookcase and IKEA logo, was on his way to a photo shoot for the IKEA catalogue with a table that he struggled to fit in his car. He took the legs off and the proverbial (LED) lightbulb went off in his head: why not design the furniture to be assembled at home by the customer, and thus save massively on transportation cost?┬Ā

Whilst IKEA does not claim that Lundgren invented the concept, he certainly contributed to bringing it to the masses and at a level that had never been seen before. The company has adopted the mantra ŌĆ£We hate air,ŌĆØ meaning that transporting the empty space inside a dresser or a table increases transportation costs, and therefore the cost to the end-consumer. Less volume, less cost, lower prices.┬Ā

Global thinking ŌĆō learning from mistakes┬Ā

In 1963, a full decade after the first showroom opened and 20 years after the company was founded, IKEA opened its first store abroad, in Norway. Another 10 years passed before IKEA established its first presence outside Scandinavia, in Spreitenbach, Switzerland, with Germany soon to follow. Germany has since become IKEAŌĆÖs biggest market with 53 stores as of 2019.┬Ā

After successfully establishing a presence outside Scandinavia, IKEAŌĆÖs global expansion marched on steadily, but not at breakneck speed. Indeed, its first attempt at establishing a presence in Japan in the 1970s went wrong due to a lack of adaptation to local expectations. Japan is a service-oriented society, and the idea of buying furniture that you then have to assemble yourself is not seen as socially acceptable. Another problem was that the standard IKEA sizes did not fit the smaller sizes of Japanese homes. By 1982 IKEA had pulled out of Japan.

Another market that experienced size problems was America, but this time the other way around. Apparently, American customers werenŌĆÖt used to such small glasses, so were accidentally buying IKEA flower vases to drink out of. But for IKEA, these experiences were all extremely valuable lessons. This is where the Nordic value of pragmatism comes in, as when the company directed its longboats towards the US market in 1985, IKEA made sure that the standard sizes of the furniture and other products it offered met the larger expectations of the average American consumer.┬Ā

Then, in 2018, the now experienced global furniture trader entered India, a country that, like Japan, does not have a strong tradition of Do-It-Yourself. But this time IKEA was ready for it; the company set up service booths where IKEA staff could help the customers put the furniture together.┬Ā

Global standard with local twists┬Ā

Based on these experiences, IKEA developed an approach to the globalisation of its business that worked extremely well: stay true to the basic concept, but make just enough local adaptations to be relevant and acceptable to local customers.┬Ā

In China IKEA introduced a range of items for balconies, as these are common in Chinese flats. It also cooperated with local businesses to provide delivery and assembly services because Chinese consumers saw it as lower status to have to assemble their own furniture.┬Ā

In Korea the company adapted its kitchen designs to incorporate kimchi-refrigerators, which are common for storing this traditional Korean side-dish. They also removed mentions of the Sea of Japan in a map of the store, instead calling it ŌĆ£The South SeaŌĆØ, which South Koreans prefer.┬Ā

The approach that IKEA follows is a combination of standardisation and localisation. Wherever you go in the world, the branding and the styles will be similar, but there will be subtle differences. The company has large teams of researchers interviewing thousands of consumers to learn about their habits, tastes and preferences.┬Ā┬Ā

Even the food offered in the IKEA restaurants is adjusted slightly to align it to local tastes. In some Chinese stores, this means offering dim sum and other local favourites on the menu in addition to Swedish meatballs, whereas in India, the meatballs are either made of chicken or are meat-free as Hindus donŌĆÖt tend to eat beef for religious and cultural reasons.┬Ā

Translation, localisation and funny names┬Ā

YouŌĆÖve heard of BILLY, but what about FR├¢SET, SM├ģSTAD, TORKIS, P├äRONHOLMEN, SKUBB or STUK?┬Ā

Exactly why IKEA founder Ingvar Kamprad decided to use place and personal names for the companyŌĆÖs various products is not really known. Some say it was to help his dyslexia, while others say that it was to give the products a more personable feel. What is certain is that IKEA has rules about what words can be used for naming products, such as character length (4-12), no family names, use of ŌĆ£├ź,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£├żŌĆØ and ŌĆ£├ČŌĆØ is a plus, the word must not be trademarked, and it must be a ŌĆ£niceŌĆØ word.┬Ā

Of course, a nice word in Swedish is not necessarily so in another language. In 2005 for example, IKEA named a childrenŌĆÖs desk ŌĆ£FARTFULLŌĆØ (meaning ŌĆ£speedyŌĆØ in Swedish) which caused a bit of a stink. The rather unfortunate connotation in English meant it had to be changed to something less gaseous for the English-speaking markets.┬Ā

But most of the time, IKEA carefully ensures that names can be used in the various countries it sells in. When opening in Thailand, IKEA took care to hire a team of Thai speakers to go through every single product name and to not only read them silently, but to say them out loud and determine if any had negative or embarrassing connotations. The work took four years but paid off; when IKEA finally opened in Thailand, all the displayed product names retained as much of the original Swedish as possible, with small adjustments made where needed.┬Ā

This means that Thai customers can happily join the long tradition of non-Scandi customers trying to read, say and decipher what those funny Swedish names actually mean, such as FYRKANTIG (square) or ├¢DMJUK (humble).┬Ā┬Ā

But even IKEA can get the balance wrong. In 2012 the company was criticised for having airbrushed women out of its catalogue for the Saudi Arabian market. In trying to adapt to the culture and norms of the Islamic country, IKEA had gone too far and created reputational damage when Western commentators, politicians and consumers started criticising these adaptations. The company issued an apology and said that it had failed to live up to its own values.┬Ā┬Ā

For the most part, however, IKEA applies the Nordic value of pragmatism and balances the universality of its products with the necessary local adjustments.┬Ā

The global language┬Ā

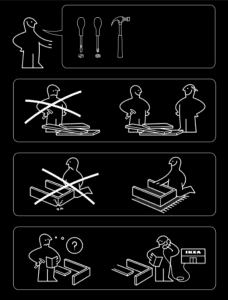

One certain way to avoid translation fails is to not have any words to translate in the first place. Albert Einstein is said to have remarked to Charlie Chaplin that ŌĆ£What I most admire about your art, is your universality. You donŌĆÖt say a word, yet the world understands you!ŌĆØ IKEA appears to have taken this on-board, because in many of its assembly instructions, such as the one shown to the right for the MICKE desk, there is not a single word in the 40 pages of instructions!┬Ā┬Ā

There is one obvious and one potential benefit from this. As with Charlie Chaplin films, no words means that in theory everyone can understand the pictures, no matter what language they speak. The potential benefit is the saved cost of having to print only one set of instructions and avoiding the cost of the translation process. I say ŌĆ£potential,ŌĆØ because when you attempt to show rather than tell, you may actually be producing documents with more pages. Translation may also be more cost-effective if it makes customers more satisfied and therefore more likely to buy another piece of furniture.┬Ā

The wordless pictograms have been another central part of IKEAŌĆÖs global approach. To ensure that the instructions are easy to follow, they ask new employees at IKEA headquarters to have a go at following the instructions and assembling the furniture. That way, they get an idea of how well the average consumer will fare. If it takes too long to assemble, they call it a ŌĆ£husband killerŌĆØ and make adjustments until it is easy enough not to drive dad to despair.┬Ā

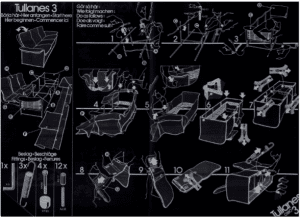

This was not true about one of IKEAs epic fails, the TULLAN├äS metal chair and sofa series, which was inspired by the car industry and in which items were supposed to be screwed together by the customer and then dressed in a cover of choice. Unfortunately, the covers, which were produced in South Korea, had such extreme colour variations that they could not be sold as sets. And the instructions, shown on the left, went down in IKEA history as the most incomprehensible ever.┬Ā┬Ā

Several of IKEAŌĆÖs mistakes, including the inflatable sofa that fell flat, the compost kitchen sofa that was a bit too organic and the pianos that could not be flat–packed, are displayed at the IKEA museum as examples of how to learn from mistakes. Kamprad himself wrote in his 1976 book The Testament of a Furniture Dealer that mistakes are permissible as long as one learns from them.┬Ā

Know what youŌĆÖre not good at

As mentioned above, IKEA is good at learning from mistakes, and that includes knowing what not to continue doing. In 2012 it launched its UPPLEVA (experience) line of TV benches with an in-built TV and speakers.┬Ā┬Ā

The design manager, Marcus Engman, admitted in an interview that the companyŌĆÖs venture into electronic technology was not a great success, saying, ŌĆśŌĆ£[it] is one area where IKEA wonŌĆÖt go. ŌĆ£We werenŌĆÖt any good there,ŌĆØ [ŌĆ”]ŌĆ£WeŌĆÖre world champions in making mistakes,ŌĆØ adds Engman. ŌĆ£But weŌĆÖre really good at correcting them.ŌĆØŌĆÖ┬Ā

This again reflects that Nordic value of being practical and realising when something strays so much from the companyŌĆÖs core expertise that the effort and cost involved in becoming good at it is more than it is worth. In other words, stop doing what you canŌĆÖt, do more of what you are good at, and keep getting better at it.┬Ā

IKEAŌĆÖs unique customer experience┬Ā

And what IKEA is especially good at is creating that unique customer experience that you can only find at an IKEA store. Walking into the huge warehouse (the biggest of which is in Manila, in the Philippines with a whopping 700,000 square feet, or 65,000m2, of floorspace), you enter an entirely new world. The stores use ŌĆ£pathwaysŌĆØ that guide you through their various film-set like exhibits, showing you (on purpose) how you might use the various products, such as furniture, utensils and cuddly toys.┬Ā┬Ā

If you are desperate to stray from the one true path, you can dash through one of the direct openings from one ŌĆ£film setŌĆØ section to another, with the openings situated so that you only miss what is relevant to the previous sections. If you want to make an early exit from the store itself however, that could prove very difficult indeed. Not impossible, just difficult; youŌĆÖre not supposed to leave without having purchased something.┬Ā

DonŌĆÖt get hangry┬Ā

In fact, IKEA-founder Ingvar Kamprad observed back in the early days of his business that customers tended to leave around lunchtime, often without having purchased anything. The simple reason was that they were hungry and needed to go home, or to a caf├® or shop, to get lunch. Kamprad realised that hungry customers buy less, and with that Nordic attitude of straightforwardness, he decided that if your customers are hungry, you feed them. In June 1960, IKEA stores only offered coffee and cold dishes, but by the end of the year, IKEAŌĆÖs restaurant kitchens were fully equipped. This included a microwave oven, which was certainly a novelty at the time.┬Ā┬Ā

Eventually, the classic dish of Swedish meatballs served up with peas, potatoes, lingonberry jam and a generous helping of cream sauce became the centrepiece of the IKEA restaurant experience.┬Ā┬Ā

Another clever move was to install large, staffed play areas in stores where a customer could leave their child to play for an hour while wandering around and looking at the products. As any parent knows, shopping with children can be a stressful experience, so being able to park them safely so that you get the peace of mind to think and choose is again a very pragmatic solution that can make a big difference.┬Ā

Translating values to value┬Ā

The Nordic values underpinning IKEAŌĆÖs business model and operating style may not be unique to the Nordic or Scandinavian countries, but the combination of these and the role they play in Nordic peopleŌĆÖs own awareness of themselves may very well mean that they play a much stronger role here than in other parts of the world.┬Ā

The Nordic self-image as a particularly democratic and egalitarian people has no doubt played a part in IKEAŌĆÖs championing of the concept they call Democratic Design, meaning a balance between five ŌĆ£dimensionsŌĆØ: function, form, quality, sustainability and low price. As Senior Designer, Sarah Fager, says: ŌĆ£Without Democratic Design, we would not live up to our vision to create a better everyday life for the many people.ŌĆØ┬Ā

Cheap but expensive?┬Ā

Although ŌĆ£the manyŌĆØ can, and indeed have, taken advantage of the cheap but well-designed products that IKEA offers, questions have also been raised about the sustainability of IKEAŌĆÖs products. IKEA has contributed, perhaps more than any other furniture business, to a change in mentality with regard to furniture. It has gone from something you invested in for the rest of your life and often handed down to the next generation to something that you buy for a much shorter time and dispose of when you want something new or the item breaks. How can this be squared with the ŌĆ£sustainabilityŌĆØ aspect of IKEAŌĆÖs Democratic Design concept?┬Ā

IKEA is aware of the reputational need to do something about this, and Marcus Engman, Chief Creative Officer for Ingka Group, IKEA, said at a panel discussion at the London Design Festival that changing consumer behaviour to become more ŌĆ£circularŌĆØ was a cornerstone in how IKEA wanted to contribute to a more sustainable future. ŌĆ£WeŌĆÖre moving into a future where waste is the raw material,ŌĆØ he said.┬Ā┬Ā

There is no doubt that, in conjunction with policy changes to encourage it, large businesses like IKEA can have an impact one way or another. When IKEA switched all its lights to LED, it instantly led to hundreds of thousands of people having less impact on the electricity grid than they otherwise would have. And it is a balance; is it not a good thing that people on tight budgets, not least families with children, can afford to make home-improvements even if there is an environmental cost?┬Ā

As Mr Engman went on to say, ŌĆ£In Sweden, where I come from, nature is in your face. You learn from an early age how to embed nature in your daily life and how to forage to fill your pantry.ŌĆØ┬Ā┬Ā

Once again, Swedish and Nordic values will show the way.┬Ā