There is much to learn from the events that made Nokia one of the greatest success stories to come out of Finland and the Nordic region, and from the challenges it has faced since. The story of Nokia is often told as a classic rise and fall narrative, with the inevitability of a Greek tragedy or the doomed fate of Norse mythology. But as with most real-life stories, nothing about what happened to Nokia was inevitable; instead, it shows us how difficult it can be to choose the best response when change happens to you, rather than the change coming from you. Read on to find out what this former Nordic giant got right and what it got wrong along the way.

Fate or choice?

In the Old Norse myths, the Norns decided your fate, right up until your dying day. There was nothing you could do to change this; you could only decide how you met your end, either as a coward or as a fighter. When we see large companies and corporations around us today, it is easy to think that they are “too big to fail”, but as several retailers in the UK have recently found out, no company is ever fully secure. Just as attacking is the best defence, driving change is the best way to remain relevant, and Nokia was a key driver of this change in the 90s and early 2000s. Then, change happened to it.

From paper mill to phones

The company that would later become Nokia started out as a paper mill in 1865, founded by the mining engineer Fredrik Idestam. The company chose the name “Nokia” in 1871 when the banks of the river Nokianvirta were chosen as the site for Idestam’s second mill.

Around the turn of the 20th century, Nokia moved into electricity generation, which caught the eye of Finnish Rubber Works. It bought up Nokia in 1918 to secure access to the company’s hydropower resources. This new entity went on to acquire Finnish Cable Works in 1922, but the three companies continued as separate operations until they were formally merged in 1967, forming the Nokia Corporation.

In the following decades, the company focussed mainly on the paper, electronics, rubber and cable markets, producing goods like toilet paper, bike and car tires, rubber wellies, TV sets, communication cables, robotics, computers and military equipment until 1979.

The new age

In 1979, Nokia entered into a joint venture with a company named Salora, a leading Scandinavian colour TV manufacturer, to create a radio telephone company called Mobira Oy. After a few years, Nokia launched the world’s first international cellular telephone system linking Sweden, Denmark, Norway and Finland, which it called the Nordic Mobile Telephone network. Shortly after, it launched the world’s first car-phone, the Mobira Senator, which weighed in at around 10 kg (hard to believe when compared to the pocket-sized smartphones we carry around today).

With this, Nokia had seized the initiative in the mobile world, at least as far as Europe was concerned. In 1987, the company launched one of the first handheld mobile phones, which, including its battery, weighed in at “only” 800 g (28 oz). The Mobira Cityman 900 was nicknamed “The Gorba” after Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev was seen using one to make a phone call during a press conference in Helsinki. The phone became the ultimate status symbol for the 1980s yuppies (young, upwardly-mobile professionals) mainly due to its high cost (more than £1600), though it only had a talk time of 50 minutes. Still, this was more than enough time to tell your secretary to book you a table at a fashionable restaurant.

The Nordic road to success

In the early 1990s, Nokia shed the divisions of its business that were not directly related to telecommunications, such as data, energy, television, tyre and cable production, focussing its corporate attention on innovation in the growing mobile phone market.

The world’s first GSM (Global System for Mobile Communications) call was made on one of its mobile phones in 1991 by the Finnish Prime Minister Harri Holkeri to the Deputy Mayor of Tampere, Kaarina Suonio. The call lasted just over three minutes but reverberated through the following decades. The year after, the first commercially mass-produced GSM phone, the 1011 (named as such because it was launched on the 10th day of November), was released to the world. This was also the first mobile phone to allow for text messaging via the Short Messaging Service (SMS) as well as roaming. But it was the launch of another innovative handset that would make Nokia the mobile phone legend it was to become.

The annoying ringtone

In 1993, the eponymous 2100 series was released. It introduced the now (in)famous Nokia ringtone, based on a short phrase from the Gran Vals in A major, a piece composed for classical guitar by the Spanish composer Francisco Tárrega in 1902. While the company had only projected sales of around 400,000 units, it went on to sell more than 20 million!

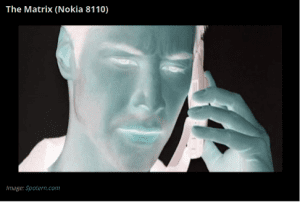

Further innovation followed in 1996 with the Nokia 9000 Communicator, which could send e-mails and faxes (remember those?), browse the internet, as well as offer word-processing and spreadsheet functionalities. That same year, Nokia launched the Nokia 8110 slider phone, which had a cover over the keys that you could slide down for dialling. The slightly curved shape gave rise to the nickname “the banana phone”, and it achieved something of a cult following after being featured in the action sci-fi film The Matrix.

Further innovation followed in 1996 with the Nokia 9000 Communicator, which could send e-mails and faxes (remember those?), browse the internet, as well as offer word-processing and spreadsheet functionalities. That same year, Nokia launched the Nokia 8110 slider phone, which had a cover over the keys that you could slide down for dialling. The slightly curved shape gave rise to the nickname “the banana phone”, and it achieved something of a cult following after being featured in the action sci-fi film The Matrix.

Yet another giant leap towards dominance in the mobile market came with the Nokia 6100 series. Almost 41 million units were sold in 1998, and Nokia overtook Motorola as the number one mobile phone maker that year. The Nokia 6110 was the first that came with the classic and addictive game “Snake” pre-installed. Nokia continued to develop, produce and sell phones at an impressive scale, and its market share climbed to more than 50% of the global market in 2007.

Why did Nokia succeed?

At this point, many articles on Nokia plunge right into the story of why the business started to falter, but it’s useful to reflect on what the company had done right up to this point. Firstly, they responded well to new and challenging circumstances. Finland had been through a recession in the 1990s and the Nokia Corporation was struggling financially. At the same time, the government had liberalised the telecoms market and Finland had joined the European Union, moving the country closer to Western markets. Nokia realised that the best growth decision was to specialise in the mobile telecoms market, so it started to divest from the non-telecoms divisions of the business.

Nokia also realised that its strength as a company lay in research and development for innovation. As Caroline Lesser writes in a paper for the OECD (Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development), called Market Openness, Trade Liberalisation and Innovation Capacity in the Finnish Telecom Equipment Industry:

“Nokia’s efficient product and process development which lie at the heart of its competitiveness — were possible in large part thanks to the company’s R&D approach. First, Nokia increased its R&D expenditure dramatically. While in 1991, R&D spending as percentage of total sales represented approx. 5.5%, this share almost doubled by 2000, to reach approx. 9%. […] “In 2005, Nokia’s R&D expenses totalled €3.8 billion, representing 11.2% of Nokia’s net sales that year.”

Focussing its operations and investing in R&D were clearly important factors in Nokia’s spectacular rise.

Nokia’s localisation strategy

Furthermore, during this time, localisation became a key part of Nokia’s success in expanding internationally. Compared to competitors like Motorola and Ericsson, Nokia found potential in adapting its products to young and fashionable consumers; part of this included localising and translating content into their languages, cultures and tastes.

Most importantly, they had to localise the product, including the software itself and support documentation, such as user guides. For example, in 1999, Nokia realised that in order to penetrate the Chinese market, one of the biggest mobile phone markets in the world, it had to develop a User Interface (UI) in Chinese. This focus on localising products helped them build connections and secure success in new global markets.

Other layers of localisation were just as important, such as Nokia’s sales and marketing materials. The localisation of these elements meant that more customers could understand what Nokia mobile phones were uniquely positioned to offer, and ultimately, decide to purchase the product. At this time, though, marketing was mostly done through traditional methods, like TV advertisements, billboards, newspapers, magazines, brochures, posters, and more. We can look back on advertisements in Spanish, Hungarian, Nepali and many other languages to see the effort that was made to connect with these audiences. Nokia’s localisation even went as far as working with local carriers, like Verizon and AT&T in the US and Movistar in Latin America, to sell its products.

Some mistakes were made too, of course, like when it went unnoticed that “Lumia,” the name of one of Nokia’s later phone models, could also mean “sex worker” in Spanish slang. Nonetheless, devoting focus and time to these localisation elements played a part in ensuring Nokia’s rise to the top, even though it turned out to be shorter-lived than the company had hoped.

Why did they fail?

In their book on the fall of Nokia, Operation Elop, the journalists Merina Salminen and Pekka Nykänen argue that the company was ill-prepared to respond to the disruptive impact of the Apple iPhone when it was introduced by Steve Jobs in 2007. Nokia had a large army of engineers who were great at developing new hardware with innovative designs and quirky functions, such as the fashion-oriented “lipstick” phone, the Nokia 7280, which features in a Pussycat Dolls music video. But as Salminen and Nykänen write,

“The product portfolio of the company was exceptionally large. This strategy had worked well while business was still blooming, even if only a small part of the company’s vast product range was successful, those best-sellers brought in enough money for the business to be successful. By 2010 the vast product range had become a burden. There had not been a best-selling product in several years […]” (Chapter 4, The lame legacy of Mr. Kallasvuo).

The beauty of Apple’s iPhone is that each new version is essentially a new and improved iteration of one product. Over the years, the content has seen the most improvement, while the physical design has changed very little. Nokia’s R&D systems were, however, more geared towards hardware than software and content.

By the late 2000s, Nokia was churning out a vast array of products. Even without a best-seller, it still shifted around 400 million units, but most of the volume was generated by basic phones priced at around 30 Euros, which did not do much to improve the bottom line. The organisation had also developed internal issues, with extremely long lead times to get phones to market and complicated management structures overflowing with internal politics.

Time to get smart(phone)

Many retellings of the Nokia story may not highlight this, but after the success of Apple’s iPhone, Nokia’s leadership quickly realised that the touch-screen smartphone was the only way forward in the industry. But even though the launch of the 5800 Xpress Music, running on the Symbian operating system, was moderately successful, with 8 million units sold, it was felt by many to have a lower quality user experience than the iPhone.

Nokia’s profits fell by 30%, sales by 3.1%, whilst Apple’s iPhone profits boomed by 330% during the same period. Then, in October 2008, the first smartphone with the Android operating system was launched, the HTC Dream, using open-source software. Nokia meanwhile continued to try and make its operating system, Symbian, able to compete with iOS and Android, but the platform was difficult to adapt. Internally, hardware designers and Symbian software designers were pulling in different directions. The sheer number of different product lines also made it very difficult to keep up to date with development in a unified manner.

Nokia’s share of the market slipped strongly from 2007 to 2010, but after 2010 it dropped dramatically. So what happened? Some point the finger at the new CEO, former Microsoft executive Stephen Elop, appointed in 2010 by Nokia’s board to turn the company’s fortunes around. As a Canadian, he was the first non-Finnish CEO of Nokia, and although some had misgivings, he was well-liked early on in his tenure.

Strategy and communication errors

Due to the problems with Symbian – it was not touchscreen-friendly and often lagged and froze – Nokia joined forces with Intel to create a new operating system, MeeGo. Development had started before Elop came aboard, but he is reported to have helped focus the development teams’ efforts on attempting to produce a Nokia product to rival even the best phones on the market.

However, for various reasons, Elop decided that the cooperation with Intel would not be continued, as he said in his now infamous “burning platform” email. In this internal memo, he used the analogy of a man standing on a burning oilrig, where he must make a choice whether to be consumed by the fire or take a chance and jump into the cold sea. This illustrated where he believed the company stood in relation to its competitors.

The email accurately set out some of the challenges that Nokia was facing, such as the high-end appeal of Apple’s phones, but when he stated that MeeGo would not be continued, along with the knowledge that Symbian was not fit for purpose, he created the twin effect of undermining consumers’ confidence in new products and increasing the pressure on the board of directors to approve cooperation with a new operating system provider. The effects were soon visible, as sales started dropping dramatically.

As a result, a cooperation deal with Microsoft was duly signed on the 21st of April 2011. On the surface, it ought to have been a match made in heaven, with the hardware masters of Nokia and the software wizards of Microsoft able to combine their efforts. However, the lack of confidence remaining in the existing Symbian OS was diminishing, as phones with this OS were being abandoned across Asia. Sales had initially held up in India and China, but device makers such as Huawei, ZTE, and Lenovo were on the rise, and Nokia’s devices were literally being replaced by Android units on the shelves. Nokia was forced to issue a market warning that revenue would be lower than expected, spooking the market and causing the share price to tumble by 18%.

Finally, in 2011, the new Microsoft-Nokia phone was born and named the Lumia, apparently for the word’s association with snow in Finnish and light in English. The Lumia went on sale in Europe in November of 2011, and from January to March the sales exceeded two million. This was not too far off the initial sales figures for the iPhone, so the hopes were that sales would climb from there. But the loss in the first quarter was 260 million Euros.

Sales in China had collapsed. In the US, the Lumia 900 had a software issue that could affect data transfer and refunds had to be offered to those affected. Moreover, Nokia’s presence as a brand in the USA was practically non-existent by 2011. The network selling the phone in the US, AT&T, soon started offering the Lumia 900 at a heavily discounted price, further damaging the Nokia brand’s image.

Critics of Stephen Elop have pointed out that in terms of market value, Nokia dropped from 29.5 billion euros to 11.1 billion euros on his watch. This ended with the unhappy sale of Finland’s flagship company, a source of great national pride, to Microsoft in April 2015.

In summary

It is too easy to say that Nokia was simply slow to respond and that its leaders were resting on their laurels. When you read the account in Merina Salminen and Pekka Nykänen’s above-mentioned book, (Operation Elop), you will see that within Nokia there was frantic work going on, including numerous realised and aborted development projects and a willingness to change and respond to changing market demands that refute this simplistic narrative of a hubristic company unwilling to accept that the world is changing around them. The fact that it appointed a non-Finnish CEO to run this national flagship company is in itself evidence of a willingness to change.

In hindsight, it is also easy to underestimate how interruptive the iOS-based Apple iPhone was back in 2007. It significantly changed the everyday world of most people in both mundane ways, like how we check the weather or hail a taxi, as well as in ways that are truly profound, like how we communicate with friends and how we interact with politics. This change was driven by the vision of Steve Jobs and the many brilliant creators at Apple, and it was a very different vision than that which had driven Nokia’s success.

Nokia was simply not prepared in its fundamental structures to adapt to a software and content-driven environment, and perhaps its greatest mistake was not to realise this soon enough. In nature, natural selection happens by the survival of the fittest. In the free market (if it is allowed to operate) the same principle goes; it is the business best prepared to meet customer demands that will survive.

But finally, let us not forget another intangible hurdle Nokia was up against: iPhones were cool. They became a fashion statement for those who wished to align themselves with what they saw as the Apple brand’s values – progressive, fresh, innovative, well-designed and quality conscious. To win against Apple you would have had to be all that, plus more fun. And you know what they say about Finns and fun…

Regardless of its later years, the Nordic company remains a great example of how taking the initiative to specialise in creating a product of relevance to people around the world, like the mobile phone, can pay off and lead to international success.