In part 1 of this article, István Lengyel, localisation industry expert and founder of memoQ and continuous localisation platform BeLazy, described the global collaboration network built for localisation services and explained the value added by each partner in the network.

In this part, he’ll examine the various technologies used by different partners. Can technology be used to eliminate partners from the network, or might it change the roles partners play in the future?

Buyers

Many localisation buyers in the IT industry used to rely on software localisation tools like Catalyst. Today, they have the choice of enterprise translation management systems (TMS) or developer-focused tools. Enterprise TMS tools manage the buyer’s content and vendors and take care of their content sources.

Some of these TMS tools, like Wordbee or Across, are on the open market, while others are offered by the largest multi-language vendors, e.g. SDL Worldserver or Translations.com GlobalLink. Some technology providers, like Lingotek or Smartling, started out as technology providers for enterprises but turned into MLVs later.

Developer-orientated tools are aimed directly at developers, and this is where tools like PhraseApp, Crowdin or Transifex become an easy sell. They speak the language of developers and are intuitive for them.

If the buyer company has an internal translator team, they prefer to use similar tools to LSPs. When I was at memoQ, we were extremely successful at selling to such companies.

Buyers have a lot of work to do on the internationalisation of their software products, and for this, little support exists. Their software needs to be properly internationalised before it can be localised – currently I am only aware of Lingoport Globalyzer supporting such tasks – and then they need to integrate the strings into their agile sprints using their continuous integration/continuous delivery tools like Jenkins or Teamcity.

Buyer-side technology is often not translator-friendly or created with the translator in mind.

Some buyer companies build their own TMS – Oracle, SAP, Netflix, IBM and Mozilla are good examples – because developing is something they do anyway. Others – like Evernote or Box – create continuous localisation platforms like Mojito or Serge. This technology doesn’t have many touch points with the translation service providers.

The problem with buyer-side technology is that it is often not translator-friendly or created with the translator in mind. It’s surprising how often the concept of the translation supply chain is completely missing from the buyer-side technology. The solution is usually to export and import the translation material with an XLIFF, but there are systems that don’t allow the translation to be imported back. Workaround solutions can easily lead to quality compromises.

In a recent survey, we at Belazy discovered that the majority of localisation buyers today have a TMS that they control. This used to be the job of the MLVs, but with the changes in technology requirements, there are more client companies that are not afraid to deploy a TMS – either cloud-based or on-premises – which is owned and managed by them.

MLVs

All language service providers (LSPs) need to have business reporting that is independent of their client’s systems. Large MLVs use business management systems like Plunet or XTRF, or develop such systems themselves. This is the technology they use internally and with their translation vendors. The systems often have APIs and customer portals that their clients can use to post their projects.

MLVs tend to prefer easily customisable web-based tools with reasonably strong translation support.

MLVs tend to prefer easily customisable web-based tools with reasonably strong translation support. If they don’t own the translation management technology, they like to buy or rent from MLV-independent software vendors like XTM, Memsource or memoQ. They prefer technology that allows the synchronisation of projects between servers, so that their vendors can work on their servers.

MLVs also develop technology to connect their clients’ bespoke content management systems to their own translation management systems. This offers then a chance to control how projects from a certain client or program are received for translation, which makes their integration work easier.

SLVs

SLVs also work with business management systems. When it comes to translation environments, they have to engage with multiple systems, either hosted by their MLV clients or by the buyer companies, or hosted by the SLV themselves, or installed locally.

SLVs tend to prefer desktop tools like SDL Trados or memoQ because they are more popular among translators.

SLVs tend to prefer desktop tools like SDL Trados or memoQ because they are more popular among translators and offer the SLV a chance to further optimise the translation projects from how the MLV had set them up. They like to standardise tools because it helps them achieve optimal production efficiency.

SLVs are in a unique, complex position where they have to create and set up translation projects in their business management system after having downloaded the translation material, assignment details and contractual documents from their MLV client’s multiple vendor portals. When they select a translator for the project, they have to reassign the work to the translator in their own translation management system.

Freelance translators

To put it bluntly, freelance translators use the technology their clients tell them to use. There are specialised, well-positioned translators who can pick and choose jobs based on what technology they are offered in, but many simply accept the clients’ choice of translation environment.

To put it bluntly, freelance translators use the technology their clients tell them to use.

How translators keep track of their projects depends on their degree of tech know-how, financial status and tidiness: while some use specialised business management systems aimed at freelance translators, others keep records in Excel spreadsheets. There are freelance translators who don’t keep track of their projects at all but trust the order data from the systems of their clients when it comes to invoicing.

Even though the up-to-date information about freelancers’ capacity to take on new work would be very sought-after data for those in the market who are constantly trying to place new tasks, there is no streamlined way for freelance translators to keep their current and potential clients informed of it in real time.

In-house translators

In-house translators work most efficiently if they don’t have to switch between translation environments too often. This is probably best facilitated at buyer companies where the tools and the content to be translated are most consistent in nature. In-house translators at translation companies work best under similar conditions, and the most productive ones are those assigned to dedicated, client-specific teams.

Summary

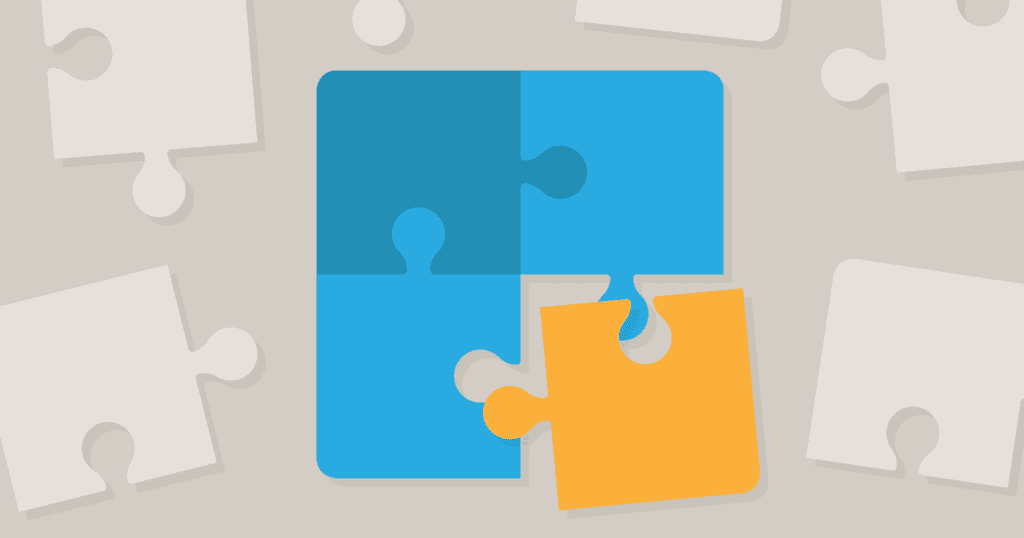

The localisation supply chain with its four partner roles is complicated, but even with time, I don’t see it changing significantly. Technology and process will remain in the hand of the buyers and MLVs. Clever SLVs will develop their vendor management role further and, instead of just delivering quality translations, contribute a quality workforce. While the ripples may temporarily shift tasks from one player to another, there are still plenty of valid reasons for keeping all four players in the supply chain.

In the table below I attempt to summarise what is the single most important task for each player in the localisation supply chain:

| Buyer | Internationalisation |

| MLV | Process management (poorly designed processes have the biggest impact on quality) |

| SLV | Vendor sourcing and translator training |

| Translator (freelance and in-house) | Linguistic expertise and quality control |