For any brand, building a connection with your global audience is a crucial part of your marketing and sales strategy. But this strategy isn’t one-size-fits-all, as your audience is made up of people from a myriad of backgrounds. So how do you show that you see each individual as more than just a number, staying true to your brand values and attracting brand-loyal customers?

One way to make your audiences feel welcome and appreciated is to communicate inclusivity through language. Staying on top of what honours the humanity of each person that interacts with your content is not just about being politically correct – it’s about showing respect for individual differences, cultures and experiences.

However, if your content spans multiple languages, it’s hard to remain an expert in all of them. That’s where we at Sandberg can help. In this article, we discuss two of the most common inclusivity conundrums and share examples of solutions for them in English and the Nordic languages.

Gender and pronouns

Did you know that the non-binary pronoun they was Merriam-Webster’s Word of the Year in 2019 because of the significant increase in its lookups? It’s a plural pronoun that has doubled as a singular pronoun for more than 700 years. Writers including William Shakespeare, Emily Dickinson and Geoffrey Chaucer all used the singular they in their work.

In the English language, there are many other invented gender-neutral pronouns today; ze, hir, E, per, xi, ip, thon, heesh, co, um and le, and some of them are older than you might think. But only they is used by everyone who speaks English, the others are used by a relatively small number of people and only in some contexts. In the English-speaking world, seeing pronouns listed in various places, such as a person’s email signature or social media profile, and the use of they as a singular pronoun, has become increasingly common.

Language that avoids bias towards a particular sex or social gender can certainly have an impact both in terms of gender neutrality and gender fluidity. All Nordic languages are working towards gender-neutral job titles, e.g. politibetjent ‘police officer’ instead of politimand ‘policeman’ in Danish, or esihenkilö ‘supervisor’ instead of esimies ‘foreman’ in Finnish. In Norway, there was even a great debate on whether jordmor ‘midwife’ should be changed, but it was eventually left untouched.

The Danish, Swedish and Norwegian languages all have gendered pronouns for the third person singular. In Sweden, the official dictionary was updated in 2015 to include a third, gender-neutral pronoun. The new pronoun hen was added alongside han ‘he’ and hon ‘she’ to refer to those of unknown gender or where gender is deemed irrelevant.

A neutral third-person singular pronoun hen or høn was also introduced into Danish, but how well it’s been adopted is difficult to say. It’s not yet in the Danish dictionary nor is it acknowledged as a pronoun by the Danish language advisory Dansk Sprognævn. Offence may be taken, however, if you don’t write gender-neutrally. If using the new pronoun feels artificial, you can write han/hun ‘he/she’ or use the word vedkommende which is gender-neutral, but sometimes difficult to incorporate into a sentence. Simply using personen ‘the person’ is also an option.

Norwegian takes a similar approach to Danish – the use of ‘he/she’ has been common, as has vedkommende in formal communication. The new neutral pronoun is hen. The national language authority Språkrådet recommends using hen for those who wish to be referred to as such but adds that it’s not yet widespread enough for them to recommend it beyond this purpose. However, even the national broadcaster NRK has started using it sporadically.

In Finnish, none of the personal pronouns are gender specific, so the existing gender-neutral third-person singular pronoun hän continues to be appropriate in modern usage.

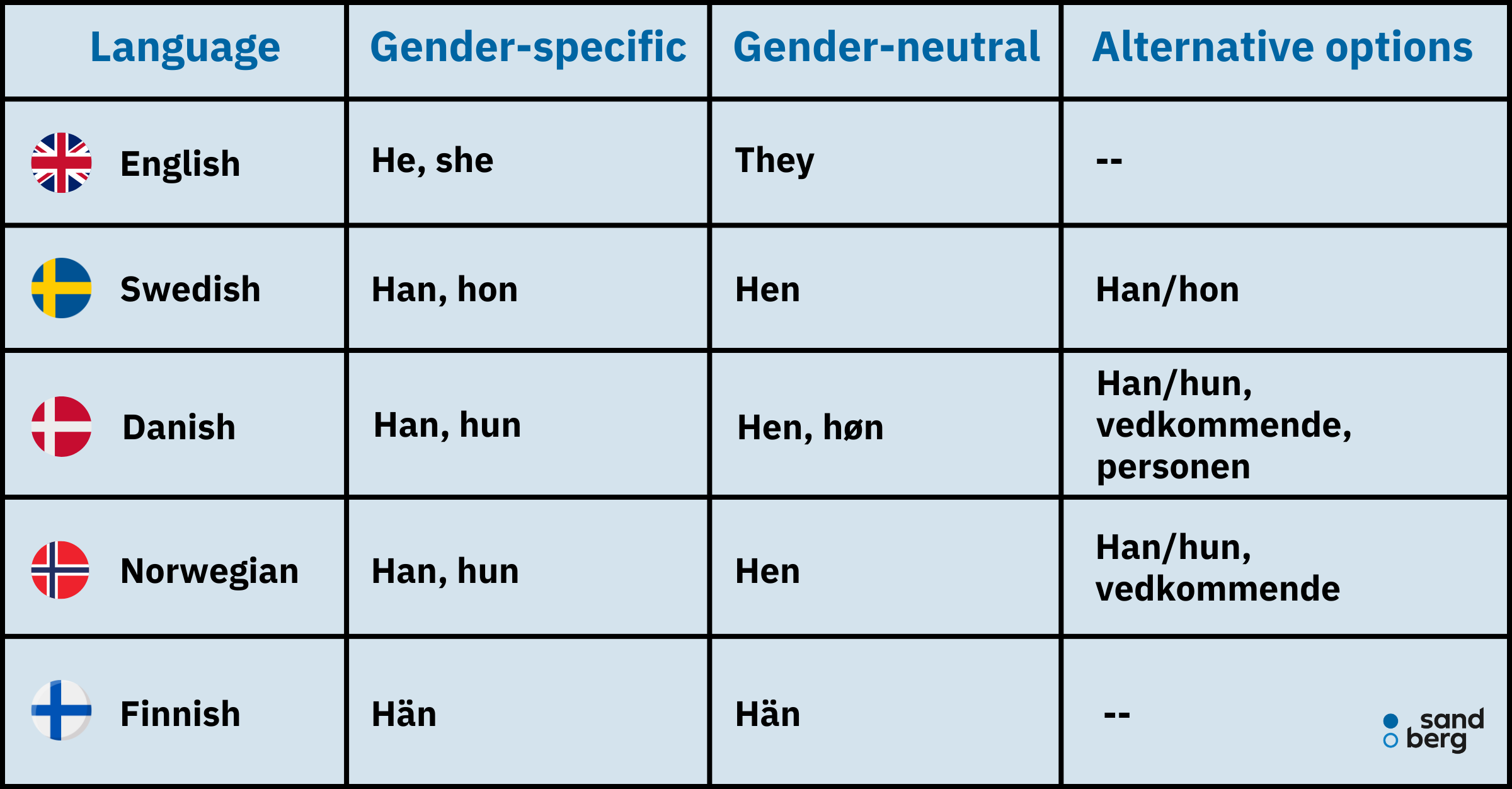

If you are in charge of content creation in the Scandinavian languages, your brand style guide should specify whether your brand wishes to use gendered pronouns, the gender-neutral pronoun hen, or any gender-neutral alternatives. The following table is a great resource to help inform your decisions.

Race and ethnicity

References to skin colour and ethnic background tend to be more common in English texts than in the Nordic cultures. In English, you can find extensive instructions on how to refer to a person’s skin colour; for example, when referring to race, you may capitalise Black but you always write white in lower case. This is because capitalising Black reflects a shared identity and culture rather than a skin colour alone. On the whole, it’s good to approach such advice with the caveat of it being correct ‘for the time being’ because what’s considered acceptable and respectful changes over time.

In the Nordic countries, people tend to avoid mentioning skin colour or ethnicity if it’s not specifically relevant in the context. They may understand expressions like POC ‘person of colour’ and BIPOC ‘Black, Indigenous, and People of Colour’ that are common in US English, but the concepts of identity behind such terms are not yet widely known in the Nordic culture. This keeps Nordic translators on their toes as they struggle to find and create equivalents that would convey the required meanings of empowerment and solidarity.

If a person’s background absolutely has to be mentioned, a neutral way might be to refer to a geographical area or region, especially if the person themselves has publicly shared it. Rather than “He is Asian,” say “He is from Beijing, China” or “He was born in Beijing but moved to the UK at the age of 5”. The rule of thumb is to be specific whenever possible, and bear in mind that even when a person has referred to themselves with a certain term, someone else using that term might still come across as offensive.

What does this mean for you?

When you wish to communicate through inclusive language in a language that you don’t speak, it’s best to work with an experienced team of linguists. In doing so, you should share brand style guides, tone of voice guides and other resources that make it clear exactly how you want to communicate with your audience so that the linguists can make the best decisions possible when localising your content. If you’re unsure of the approach to take in the target language, consider consulting with linguistic and cultural experts first to understand how far some of the newly coined expressions have been adopted in different languages and cultures.

It’s good to remember that your choice of words is never just about the person or topic you are writing about. It’s also revealing about you and the brand you represent. When possible, ask people which pronouns and terms they wish to use about themselves. By showing respect and inclusivity through this process, you can build a more diverse and loyal global audience.